Too many hardworking, highly skilled farmers quit simply because they can’t afford to pay their bills. A love of the job and a passion for the cause and the quality of the food cannot sustain them for long. Lifestyle choices such as having children or owning and improving land are not viable options for many new farmers.

Consider this: the number of farmers under the age of 45 dropped 14 percent between 2002 and 2007, and the number of farmers over the age of 65 increased by 22 percent in the same timeframe. Yet, if we want the majority of our food to come from diversified small-scale, local farms, we must increase the number of young farmers rather than watch them try out farming only to move on to more lucrative occupations.

Improving the income of small-scale farmers amidst the prevailing “cheap food” mentality is a daunting task, but we can begin by addressing the underlying issues. We must:

1. Shift government agricultural subsidies away from monoculture, large-scale commodity production to diversified small-scale farms.

The top five crops subsidized in the United States are corn/feed, cotton, soybean, wheat, and tobacco. Since their inception in the 1920s, these subsidies have increasingly gone to larger farms. In the 1930s, 25 percent of the population lived on 6 million small farms across the country. But by the turn of the century, roughly only 150,000 farms accounted for 70 percent of the nation’s total farm sales, which are largely commodity crops.

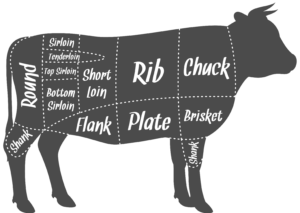

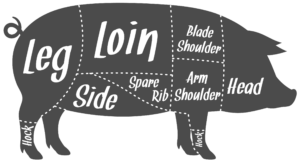

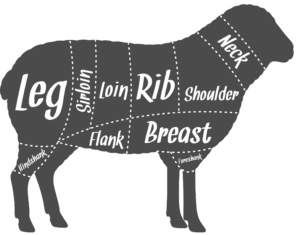

The artificially low commodity prices induced by subsidies economically disadvantage the farms that do not receive them—typically smaller and diversified operations. In developing countries, local farmers are forced out of the marketplace and even off their land when subsidized goods enter foreign markets at costs that unsubsidized local farmers cannot compete with. As a result, around the world, unhealthy processed foods have become cheaper than healthy fresh foods. Diversified farms that produce high quality fresh vegetables and grass-fed meats and milk should be subsidized rather than commodities that end up in unhealthy processed foods.

2. Reduce competition from large-scale monoculture-style operations that attempt to capitalize on the demand for ethically produced food.

In many cases, the USDA certified organic food in mainstream grocery stores comes from farms and businesses that do not provide the benefits to society that the term “organic” originally signified. What was once a movement led by small-scale, diverse, local, family farms has now become dominated by industrial-scale farms that simply substitute organic inputs into mono-cropping production systems or — even worse — cheap imports from potentially fraudulent sources. These operations are corporate entities, distributing food nationwide, sometimes globally; their production systems do not always incorporate ecological principles or benefit local communities.

Today, the words “organic,” “local,” and “family farm” have all been co-opted by agribusinesses in an attempt to exploit the increased demand for quality food. Educating consumers to “know their local farmers” and, when locally produced foods are not available, to buy from ethical organic brands, is paramount to reclaiming original organic principles.

3. Increase opportunities for farmers to own farmland close to their markets.

Farmland close to cities is much more expensive than land further from town. Often, new farmers are forced to live far from their customer base, making marketing much more difficult and expensive.

Deliveries must incorporate time and gas spent driving into town, creating fewer opportunities to direct-market fresh produce. Some farmers choose to rent land close to town, but will never have the opportunity to own and, therefore, make long-term investments in the land.

Programs that finance and support alternative ownership of farmland close to town need to increase. For example, Equity Trust is a nonprofit that actually pays the difference between the agricultural and market values so farmers can afford to buy farmland that is of interest to developers and the rural real estate market. USDA subsidies for low interest loans to farmers also should be expanded. Farmers deserve the opportunity to own their own land, and to farm close enough to their market that their consumers are able to know them and their farming practices.

Educating consumers on the ethics of food production needs to continue. The benefits from sustainable production to the environment, local economies, and human health are well studied but not reinforced in our culture. Homegrown food from highly diverse, sustainable farms can be more expensive than processed food and unobtainable for many people.

Unfortunately, short-term savings result in long-term costs affiliated with pollution, failing local economies, and skyrocketing healthcare costs. What would the true price of processed food be if subsidies to commodity crops were eliminated, and the costs of pollution, migrant labor, and healthcare were incorporated?

Unless we, as a society, begin to tackle these issues in earnest, with the goal of achieving a paradigm shift in our food supply system, nothing will change. Small-scale, family farmers will come and go while monoculture agriculture will continue to assail us with pollution and inferior nutrition.

All of the momentum that has built up over the past decade surrounding responsible growing and eating will mean very little if an honest effort isn’t made to support the people capable of producing superior food.

Condensed from an article by Linlay Dixon, PhD and published by the Cornucopia Institute. To read the complete article, click here