By Andrew Amelinckx on August 8, 2016

Reprinted from http://modernfarmer.com

On July 29, President Barack Obama signed a bill into law requiring the labeling of food containing genetically modified ingredients, following a drawn-out battle between the food industry and pro-labeling groups on the issue.

As much as 75 percent of the food Americans get at their local supermarket includes genetically modified ingredients, so no matter if you’re anti-GMO, pro-GMO, or aren’t really sure where you stand on the issue, you’ll be affected by the new law in some way. The exact specifics, however, are a little complicated, so let us break it down for you.

What does the new law say?

The new law came about as a compromise after an earlier version of the bill failed to garner enough support in the U.S. Senate. The earlier version passed by the House in July 2015 would have made GMO labeling a voluntary program. You can read more about the original bill here. The bill President Obama signed into law makes labeling mandatory, but is vague on details, leaving a lot of the specifics of the program up to the USDA.

What will the new labels look like?

A Vermont law that went into effect in July (but was nullified by the new federal law) forced food companies in that state to clearly declare on the label whether there were genetically modified ingredients in a product. The federal version, though, gives producers several options to identify GMOs. (This was the big compromise that likely got the bill passed.) Producers can choose from a few options: words on a package’s label; a symbol (which hasn’t yet been designed; the law isn’t specific about if will be a universal symbol); a 1-800 number that consumers must call to get information on the product’s genetically modified ingredients; or a QR code that has to be scanned with a smartphone, which will take the consumer to a website for GMO information. Pro-labeling advocates—including Andrea Stander, the executive director for Rural Vermont, a grassroots organization that supports small farmers—believe a large percentage of consumers, mostly poor, elderly, and folks in rural areas, “will have no way to access the information that the companies choose to provide through digital technology,” she says.

Which of these options major food companies will choose is an open question at this point. “Since the bill was just signed into law and the rules and regulations have not been developed yet, it is too early to say what companies will do when the regulations are finalized. In addition, each company will make its own decision,” Roger Lowe of the Grocery Manufacturers Association, a trade group for the food industry that supported the new law, tells Modern Farmer in an email.

When will the labeling law go into effect?

The USDA has two years to finalize the regulations. The law isn’t specific about how long food companies have to start labeling their products after the regulations are finalized, but small producers—defined by the FDA as having less than 500 employees—will have one year longer than larger companies, like, say, Nestle. Tiny food companies—defined as making less than $1 million in sales per year from human food—will be completely exempt, as will food served in restaurants and other food establishments, based on the law’s language.

What products will have to be labeled?

The most ubiquitous genetically-modified agricultural crops—corn, soy, canola, and sugar beets—would require labeling in their unrefined state. But as the FDA points out, many highly-refined products that come from genetically-modified sources, such as oil made from soy or canola, will not have to be labeled because they don’t fit the law’s definition of “bioengineering” and don’t necessarily contain genetic material.

“My understanding is that many, many common types of food ingredients such as oils and sugars will be exempted from labeling under this law; things like corn syrup and soybean oil which are pretty ubiquitous in processed food,” says Stander. The FDA‘s reading of the law is in line with what Stander says, but it will ultimately be up to the USDA Secretary of Agriculture to decide what exactly will and won’t be required to be labeled.

As we noted back in April, genetically modified fresh food is far less common, though there does exist GM sweet corn, papayas from Hawaii, and yellow squash, all of which would have to be labeled. Some genetically-modified produce has recently been approved by the FDA, including apples and potatoes, as well as salmon (though none of these have made it to the supermarket yet)—they’ll have to be labeled, too.

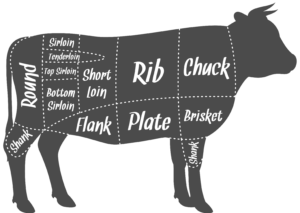

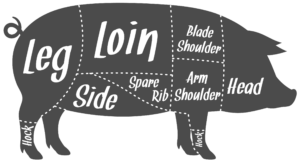

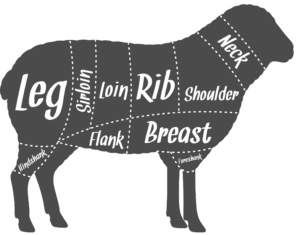

Meat and other products, like milk or butter, from animals that consumed GMO feed, will not have to be labeled.

It should be noted that organically-produced products are by definition non-GMO, and the law now allows producers who are certified organic to put a “GMO-free” label on their products without having to go through a third-party certifier.

Will we be seeing a rise in food prices?

Lowe didn’t say whether this new law would mean higher prices at the checkout, but did say he believed it “will be less costly and confusing to consumers” than if the states were allowed to create their own individual labeling laws.

What if I want to find out right now if my food contains GMOs?

Lowe points out that 10 companies, including General Mills and the Campbell Soup Company, are already providing information on GMO ingredients, among other detailed information about their products, through the SmartLabel initiative, which launched in December 2015. Genetically modified ingredients found in the various products are listed under the “other information” tab on the website. But, like the federal law that will allow companies to use a QR code, you have to either have a smartphone or a computer in order to access the information.

Your best bet right now is to look for foods that carry labels from the Non-GMO Project, A Greener World’s Certified Non-GE, or USDA organic labels.

What’s the controversy surrounding the law?

The FDA maintains that food containing GMOs are as safe to consume as non-GMO food. Groups such as the Center for Food Safety believe there hasn’t been enough testing to definitively prove GMOs are safe to eat, and additionally pose risks to the environment through cross-contamination of plants and the use of more chemicals on GMO crops.

So who’s happy about the law and who isn’t?

Many pro-labeling groups, like the Center for Food Safety, Rural Vermont, and Just Label It, didn’t support the compromise legislation, which they feel is a much weaker version of the Vermont law. Other groups like the Organic Trade Association (OTA), and companies like Whole Foods Market, supported the law’s passage, since, according to the OTA, the law is “a constructive solution to a complex issue.”